An Object-Oriented Framework for Pre-Election Rumors

The "What to Expect When We’re Electing" Series

By Kate Starbird, Ashlyn B. Aske, Danielle Lee Tomson, Joseph S. Schafer, Stephen Prochaska, Adiza Awwal, Rachel Moran-Prestridge and Michael Grass

Key Takeaways:

This “What to Expect When We’re Electing” piece aims to support election officials and journalists in identifying recurrent tropes, themes, and narratives around election processes and procedures.

This piece offers an “object-oriented framework” for organizing the types of rumors that we expect to see emerge in the lead up to the November 5 election.

We offer examples and explanations of rumors around rules, voter rolls, ballots, voting sites, machines, voters, and lastly, officials, workers, and observers.

This is not an exhaustive list and focuses on registration, mail-in voting, and in-person early voting phases of the election. We have plans in mid-October to write a follow-up article for the Election Day and vote-counting phases.

It’s early October and the 2024 U.S. general election is kicking into high gear. Registration efforts are ongoing, with deadlines approaching in some states. Mail-in ballots are being printed in some locations, and are already out the door in others. Early in-person voting is just around the corner. Political turmoil around the election is (arguably) at an all-time high, with assassination attempts against candidate Donald Trump and late-stage changes to the Democratic ticket. Meanwhile the echo of “voter fraud” claims from 2020 continue to bounce around an increasingly volatile, yet fragmented information ecosystem. All of this — the anxiety and uncertainty of the election, the chaos of our political moment, and lingering conspiracy theories about the 2020 election — set the stage for a period of intense rumoring about voting and election processes in the coming weeks.

Rumors are inherently emergent and dynamic, making them hard to precisely predict. However, our past research on rumoring in general — and election rumors in particular — can provide insight into the kinds of rumors that we might see this fall. For example, we know the most effective and potentially viral rumors often combine a novel element (like details from a recent event) with a familiar theme (“non-citizen voters”) or trope (e.g., “suspicious white vans”). Additionally, we know that most misleading rumors about election integrity either feature speculation without evidence or mislead by twisting evidence in five common ways: fabricating or manipulating evidence, misinterpreting/mischaracterizing evidence, obscuring remedies, exaggerating impact, and falsely attributing intent.

In this article, our research team presents an “object-oriented framework” for organizing the types of rumors that we expect to see emerge in the lead up to the November 5 election. This piece is organized by the different “objects” in an election: rules, voter rolls, ballots, voting sites, machines, voters, and lastly, officials, workers, and observers. Because election rumors on social media often feature “evidence” in the form of photos, videos and eye-witness accounts of specific aspects of the election process, this object oriented framework organizes rumors by their common subject matter. This is not an exhaustive list and we are focusing on the registration, mail-in voting, and in-person early voting phases of the election, with plans to write a follow-up article for the Election Day and vote counting phases in mid-October. This framework highlights the different components of the election process that we expect to provide both novel elements and familiar tropes that are likely to spawn new rumors about election administration in 2024. Our hope is that this framework can help others prepare for and/or quickly respond to rumors that we anticipate will emerge in this cycle.

The Rules

Rules and laws about registration, voting, vote-counting, and certification often feed rumoring about election administration. This is especially true in the U.S. because — since the job of administering elections is distributed at the state and local levels — rules vary across thousands of different jurisdictions. This variability and complexity creates real confusion that can lead to organic rumors or be exploited to spread intentional falsehoods that can disenfranchise voters and diminish trust in the election process and its outcomes. Late stage changes to the rules governing election administration can compound these issues, contributing to a more confusing and chaotic information space, fueling additional rumors. The rules guiding how elections are administered are also increasingly the site of political machinations — for example, efforts to remove third party candidates at the last minute or decisions to hand count ballots — that can disenfranchise voters, cause delays, diminish trust in the process, and generally enhance uncertainty and anxiety about the process and results. During the pre-election period, we are likely to continue to see politically-motivated attempts to challenge and change the rules, which often give credence to past rumors and will inevitably seed additional ones.

Rumors about when, where, and how to register and/or vote

Examples:

Election systems in Mississippi accidentally sent voters to the wrong polling location, prompting confusion and rumoring (2020).

Political activists used social media to attempt to convince Hillary Clinton voters they could vote via text message, which was false (2016).

Explanation: When false, rumors about registration and voting processes are particularly problematic, because they can disenfranchise voters and aggravate distrust in elections. Some of these rumors will emerge from genuine confusion. Others may be sparked by errors in election systems or miscommunication by election officials. A few rumors may result from deliberate deceptions. Intentionally misleading people about when, where, and how to vote is considered a form of election interference, and has been prosecuted for violating federal law in the past.

Late-stage changes to the rules contribute to confusion and speculation

Example: The Georgia State Election Board’s recently passed rules, including a requirement for counties to hand-count all ballots cast on Election Day, sparking rumors about political intentionality (2024).

Explanation: Late-stage changes to the rules can contribute to the confusion about when, where, and how to vote; as well as the processes of counting and certification. Additionally, these changes are likely to set off speculation around intentionality — i.e., claims that the changes are politically motivated and designed to give one party an advantage over another, which can reduce trust in the process and results. New rules in Georgia have been widely criticized for their potential to cause chaos, confusion, and errors — which would likely add grist to the rumor mill. These and other changes have also garnered accusations of potential partisan motivations. The Georgia Attorney General’s Office has raised concerns that the new rules there likely exceed the Georgia State Election Board’s authority — leaving them open to legal challenges that could further foment uncertainty leading up to the election.

Voter Rolls

Voter registration records (also called voter rolls) are another focus of election administration rumors. Often, these rumors seize upon perceived inaccuracies in the voter rolls to falsely imply that large numbers of ineligible people are able to vote — and therefore that election results cannot be trusted. At the more extreme end, conspiracy theories allege without evidence that “loose” voter rolls enable and/or signal systematic election fraud by organized entities. Claims of loose voter rolls can be evidenced by actual, though isolated, cases where voting materials like registration forms and ballots are received in error, or through mischaracterized analyses of public voting records. These claims invoke an ongoing political debate, resonating with efforts that may prevent potential fraud but also raise the burden of registration in ways that can disproportionately impact minority voters. Rumors casting doubt on the security and accuracy of voter rolls may also include allegations that rolls or electronic poll books are susceptible to hacking by foreign governments (or other adversarial actors).

Rumors about ineligible voters — e.g., “non-citizens,” dead people and pets — registering or registered to vote

Examples:

Rumors leveraging public voter data falsely suggested that people over 100 years old were registered to vote in Michigan, feeding untrue rumors of large numbers of “dead voters” (2020).

An X user claimed to have discovered “suspiciously large” numbers of people registered to vote at a single address in Seattle, Washington through accessing publicly available data about voter registrations (2024).

Misleading claims that thousands of non-citizens were removed from voter rolls in Alabama, Texas, and Virginia (2024).

In August 2024 Fox News Business host Maria Bartiromo claimed that non-citizens were registering to vote near Department of Motor Vehicle locations in Texas.

Explanation: Rumors about ineligible voters on the rolls often mislead through misinterpretations or mischaracterizations of so-called evidence or relevant laws, or by obscuring remedies that would address the issues elsewhere in the election security process. Voter rolls may contain errors or anomalous formatting, as in the claims about dead voters in Michigan. Misunderstandings of how voter rolls are maintained and of the relevant state, federal, and local laws lead amateur data sleuths to misinterpret what appear to be anomalies in voter rolls as evidence of fraud or negligent voter roll maintenance practices. In the Washington case, the large numbers of “suspicious” registrations were actually associated with unhoused people registered to vote at homeless shelters (which is legal in Washington).

Similarly, claims that non-citizens can register to vote while getting a driver's license misinterpret evidence through misunderstanding the purpose and requirements of the National Voter Registration Act. States are required to provide opportunities for people to register to vote in various contexts, including alongside applications for driver’s licenses, in order to make it easier for all eligible voters to register to vote and maintain accurate records. Additionally, filling out a voter registration application does not necessarily guarantee someone will actually be registered — security measures exist to ensure that ineligible individuals’ applications are rejected. In any case, non-citizens are particularly unlikely to fraudulently register to vote given the significant criminal penalties and risk of deportation. In instances like the claims about non-citizens being removed from voter rolls in various states, rumors may misinterpret evidence due to misunderstandings of voter roll maintenance procedures. Processes that initially identify individuals as non-citizens on voter rolls don’t always account for people who have recently become naturalized citizens; thus officials in Alabama did not actually remove flagged individuals but instead changed their status to inactive until updated information confirmed their citizenship.

Rumors and conspiracy theories about voter roll maintenance systems and procedures

Example: Conspiracy theories falsely alleged that the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), a tool used by election officials in multiple states to aid in voter roll maintenance, disproportionately benefits Democrats, or has financial ties to non-state partisan individuals or organizations.

Explanation: ERIC is a bipartisan initiative founded by state election officials for states to share voter roll data in order to clean voter rolls, ensure accuracy, and encourage voter registration. The system was founded by state officials with seed funding from Pew Charitable Trusts, a non-profit organization dedicated to improving public policy. ERIC’s primary role is to help state officials identify where the same voter is registered in multiple states and to remove those duplicate registrations from the voter rolls — in other words, ERIC helps to make voter rolls more accurate.

However, ERIC became the subject of pervasive conspiracy theories, which National Public Radio detailed in a 2023 article. Though ERIC is now funded by its member states, many of the conspiracy theories fixated on ERIC’s initial funding by the Pew Charitable Trusts, and particularly on the fact that Pew received funding at one point from Open Society Foundations. Open Society was founded by billionaire and frequent conspiracy target, George Soros. Though Soros played no role in its connection to Pew or ERIC, conspiracy theorists connected the dots, claimed that Soros was funding ERIC and staffing it with liberal employees who would pad the voter rolls with liberals. Such theories prompted Trump to claim that ERIC was “pump[ing] the rolls” for Democrats. The conspiracies have prompted some states to pull out of the partnership. Unfortunately, in stepping away from the program, states have lost an important mechanism for maintaining accurate voter rolls, which could lead to more issues of voters being registered in multiple states and therefore more rumors about untrustworthy elections. This is another case where false rumors about election integrity have led to changes in election administration that will cause more uncertainty and confusion, potentially fueling more rumors about and more distrust in the process and results.

Ballots

Ballots are both a mechanism and a symbol of democracy, giving them both political and emotional salience during the period around the election. There is also both a familiarity and an inherent novelty to ballots, as they are easily recognizable but only present in our lives for brief periods each year. Additionally, they are physical objects that have the potential to be moved, destroyed, or altered, as well as photographed, making them popular objects to “evidence” a rumor. Ballots thus feature in many of the common tropes and prevailing frames about election administration. For these and other reasons, rumors about ballots may be stickier and have more viral potential than others.

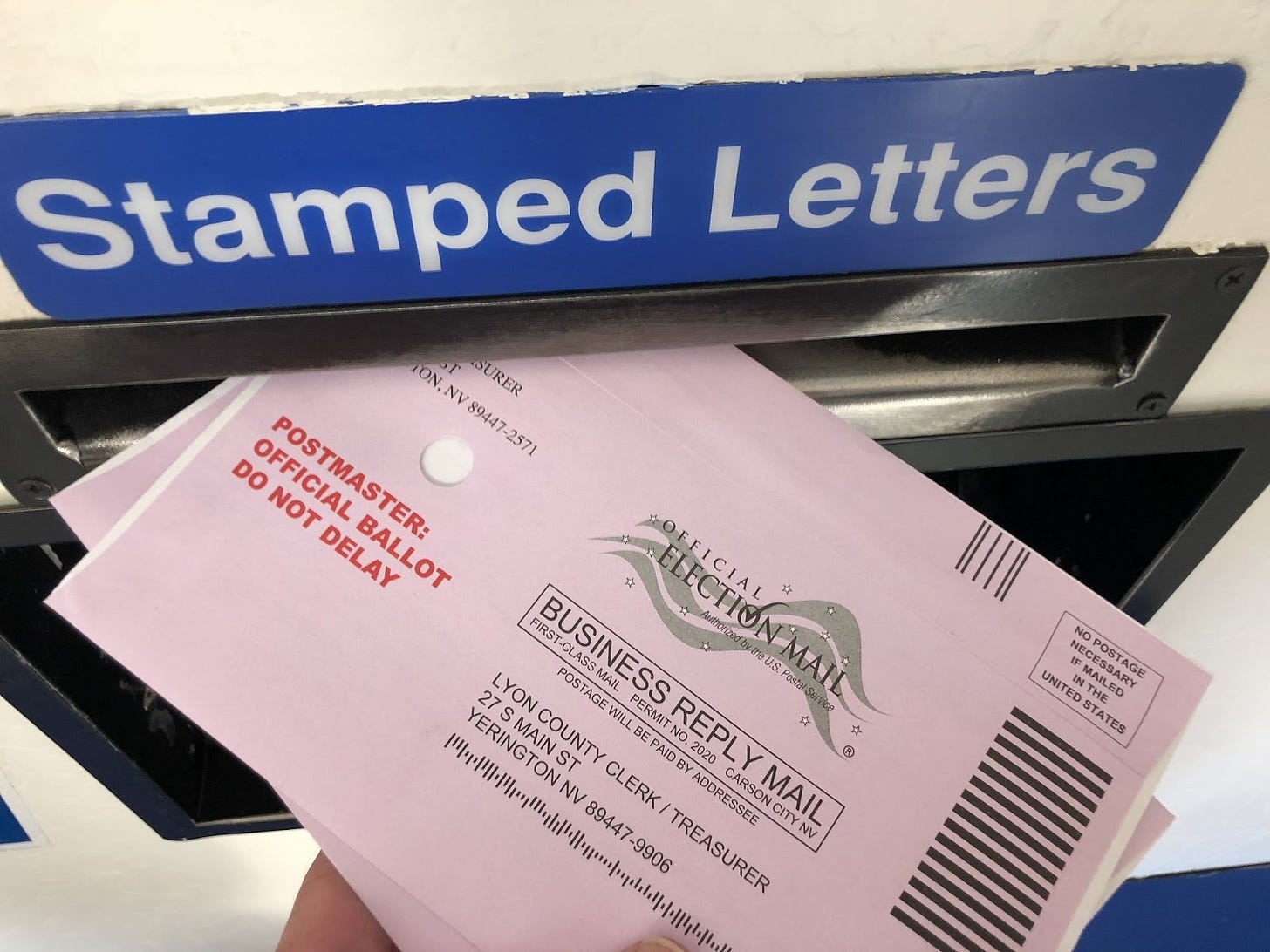

Rumors about mail-in ballots lost, found, stolen, discarded, dumped, or delayed

Examples:

Video claiming to show mail-in ballots being discarded and shredded (2020).

Reports (and a photo) claimed that “thousands of ballots” in a dumpster in California (2020).

A temporary contractor claimed that mail-in ballots were discarded in Pennsylvania (2020).

Photos of ballots discarded in California and New Mexico incited false rumors of election malfeasance (2022).

Explanation: As mail-in ballots make their way through the postal system from election officials to voters and back again, there will inevitably be rumors about ballots that get lost, stolen, or discarded along the way. These rumors will often feature compelling “evidence” such as photos of ballots — or materials perceived to be ballots — found in dumps, ditches, or other strange places. At times, these ballot rumors may be misinterpretations. For example, in 2020, a viral rumor claimed that thousands of mail-in ballots had been found in a dumpster in California, feeding a broader narrative that mail-in voting was untrustworthy. The rumor featured a photo of what turned out to be ballot envelopes, not ballots, from 2018 (they were being recycled at that time according to the law). In other words, the “evidence” of discarded ballot materials was normal election procedure and had nothing to do with the 2020 election. Very similar rumors spread again in 2022 in California and New Mexico. In other cases, evidence of real — though isolated — issues with ballots are used to fuel rumors that exaggerate their impact, overlook remedies, and falsely attribute intent. Unfortunately, postal workers do sometimes fail to deliver mail and mail-in ballots do occasionally get stolen (along with other mail) from mailboxes, but these issues are rare, are almost never motivated by political objectives, and have a simple remedy. Whatever the cause, if a voter does not receive their mail-in ballot in a timely manner, they can request a new one, and election systems will void the original. When ballots are found in odd places, they can be returned to the voter or destroyed and reissued by election administrators.

Rumors featuring registration forms or ballots received in error — e.g., a voter receiving multiple registration forms or ballots, forms or ballots mailed to the wrong address, or registration forms mailed to an ineligible person

Examples:

A couple received multiple mail-in ballot applications addressed to people who didn’t live there and mistakenly believed the applications could be used to request multiple ballots in Illinois (2020).

Claims that dogs received voter registration applications, in Colorado (2018) and North Carolina (2016) sparked rumoring.

A spokesperson’s words were taken out of context that thousands of pets, and dead people, received ballots in Virginia and Nevada, fueling rumors (2020).

Explanation: These rumors often feature a photo or first-person description of the errant voting materials as evidence to support questions and/or allegations about loose voter roles. The evidence itself is often real, but the rumors that build upon errant voting materials to question the integrity of the election often either misinterpret the evidence (i.e., the materials are often registration forms, not ballots) or overlook remedies that would address the issue later in the process. Though many of these claims (including the Virginia and Nevada rumors in 2020) begin with allegations about ballots, the materials in question usually turn out to be registration forms. And though registration applications are sometimes mailed in error, downstream security measures would typically prevent both multiple registrations by one person and ineligible people from registering. And in cases where a person did receive two ballots, ballot security measures prevent two ballots from being counted.

Rumors about pets registering, receiving ballots, or voting are a useful (and recurring) example of misinterpreted evidence, falsely attributed intent, obscured remedies, and exaggerated impact. Almost always, the issue is with pets receiving registration forms, not ballots. Some of this results from overly-enthusiastic civic organizations sending out registration forms based on unreliable data, a practice that election officials have criticized for leading to confusion, but one that is unlikely to reflect an intentional effort to perpetrate fraud. In the North Carolina example, a man registered his phone number in his dog’s name, which may have contributed to the error. In the claims about Virginia and Nevada in 2020, rumors about large numbers of pets receiving ballots gained prevalence after a spokesperson for a civic organization shared an anecdote about a similar error that led to one dog receiving a mail-in ballot application. The rumors about pet voting greatly exaggerated their prevalence, suggesting that isolated cases like that one reflected a widespread problem that could impact the results of an election.

Rumors about errors, ambiguity, or perceived unfairness in ballot design

Examples:

The poorly-designed “butterfly ballot” used in Florida for the 2000 election confused voters due to misaligned candidate names and marking spots.

Claims that holes in ballot envelopes for California’s 2021 recall election revealed voter’s selections (similar claims have come up in many elections).

Allegations that indications of party ID on the outside of the envelopes in Washington state are a vector for election fraud, when they are only for the presidential primary.

Claims that a candidate’s name falls in the same place where the ballot is folded, disadvantaging that candidate (noted in 2024 New Hampshire Primary).

Tim Walz’s name being misspelled on a Florida ballot and Kamala Harris being left off of Montana overseas voter ballots incite rumoring about intent of officials (2024).

Explanation: Flawed ballot design is a real threat to election integrity. Recent history provides a few rare, but noteworthy cases where ballot design issues have possibly impacted election outcomes (as in 2000 with the infamous “hanging chads”) and resulted in discrepancies in election results (as in Windham, New Hampshire in 2020). In the rare cases where election outcomes are potentially impacted by ballot design, the issues are unlikely to be intentional. Some notable rumors about ballot design therefore mislead by falsely attributing intent to real design issues.

However, most rumors featuring perceived issues with ballot design reflect misinterpretations of evidence and/or misunderstandings of election processes (including overlooked remedies). For example, a common conspiracy theory alleges that holes in ballot envelopes are a vector for election fraud, but they are instead a recommended practice to make voting accessible for people with disabilities. In the New Hampshire’s 2024 primary, another type of rumor raised concerns that presidential candidate Trump would be disadvantaged, because in some voting locations his name was printed along a fold in the ballot, overlooking the fact that candidate ordering is randomized in different jurisdictions, meaning no candidate is systematically advantaged/disadvantaged by consistently being listed first, last, or on the fold. Recent cases stemmed from the news that Tim Walz’s name was misspelled on ballots in Florida and Kamala Harris’s name was left off of overseas voter ballots in Montana. Though the errors were quickly corrected, false rumors spread among Democrats that the mistakes were intentional. In some places, those false rumors were synthesized with unrelated criticisms claiming Republicans are changing election rules for their political advantage, in support of a broader narrative that Republicans are cheating in the 2024 election.

Rumors around the legality and fairness of “Ballot Harvesting” — allowing others to collect and return absentee and mail ballots

Examples:

Claims that Ilhan Omar and others committed fraud via ballot harvesting in Minnesota in 2020 primaries.

Social media posts claimed that CNN depicted ballot harvesting in Ohio (2023).

A debunked conspiracy theory was promulgated by a documentary (that was retracted by its original distributor) that “ballot mules” perpetrated systematic fraud by depositing harvested ballots into public dropboxes (2020).

Explanation: Most states permit someone besides the voter to return a mail or absentee ballot — a practice referred to as “ballot collection” or “ballot harvesting”. The exact rules around who can drop off ballots vary widely by state, inspiring confusion over what is legal in a particular location. Further, partisan disagreements have developed over the practice, with many Republicans arguing that organized ballot collection, particularly by political volunteers and operatives, is a vehicle for fraud. In 2022 Dinesh D’Souza’s widely debunked and subsequently retracted “2000 Mules” documentary argued that the 2020 presidential election was rife with “ballot trafficking” — an inflammatory name for ballot harvesting implying illegality — by coordinated “mules” (akin to drug mules). Rumors around ballot harvesting are often facilitated by false or manipulated evidence, where videos purporting to show ballot harvesting are often reliant on heavily-edited videos. For example, in 2020 a widely-shared and selectively edited video claimed to show an operative illegally collecting absentee ballots en masse and falsely insinuated that the effort was conducted on behalf of Ilhan Omar. Finally, these rumors can exaggerate impact, where ballot harvesting is portrayed as a far more prevalent, impactful phenomena than evidence indicates.

Voting Locations

Voting locations, such as polling stations and ballot drop boxes, are routinely featured within rumors about election administration. Rumors about location closures, violence at polls, or long lines can have a disenfranchising effect on the public — regardless of the veracity of the rumor. Additionally, ballot drop boxes have become locations both for rumoring, with accusations that they are insecure, and for mobilizing around those rumors. Some activist and political organizations, including the Republican National Committee, have launched monitoring efforts that include in-person surveillance and livestreams of drop box locations. Some officials fear will lead to voter intimidation.

Rumors about “emergency closures” and other issues with physical voting spaces

Examples:

Rumors of voter suppression after an early voting site was evacuated due to a bomb scare (2022).

Rumors that the closure of a Texas polling station was an intentional attempt to suppress voters.

Explanation: Emergency closures of polling locations — whether due to security threats or maintenance issues — can result in speculation that these disruptions undermine election integrity and allegations that they reflect an intentional effort to disenfranchise voters. Threats that close polling locations can indeed impact voters, forcing election officials to provide remedies and raising the burden on voters (who may have to go to another location). Some voters may even lose their opportunity to vote. However, in the vast majority of historical cases of polling location closures, the impact on election processes is minimal and the cause is rarely politically motivated. For example, the bomb threat that closed the early voting site in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood in 2022 was against a nearby school and likely not related to the election. Similarly, the Texas polling station was closed on Election Day in 2022 because a worker had been accidentally electrocuted there. Rumors and conspiracy theories about closures often mislead by exaggerating impact, obscuring remedies, and falsely assigning political intent to the cause.

Rumors about protests and/or potential violence at the polls

Examples:

Rumors that “Army for Trump” poll observers were a voter intimidation effort (2020).

Allegations that “under surveillance” signs put up near ballot dropboxes constituted voter intimidation (2022).

Democrats receive emails threatening violence if they vote from a group posing as the Proud Boys, though the Department of Homeland Security discovered Iran was to blame (2020).

Explanation: Regardless of veracity, rumoring about potential violence at the polls — e.g., speculation about armed protesters at polling locations — can intimidate voters and suppress turnout. This kind of rumor is particularly challenging though because the stakes are incredibly high and if the rumors of violence are true, it would be important for people to take protective action. Rumors about violence may come from a targeted group trying to raise awareness that they may be vulnerable, though it may inadvertently suppress the votes of that very group. For example, in 2020 left-wing influencers framed efforts by the Trump campaign to mobilize poll observers as threatening violence, though the “Army for Trump” effort was likely designed not for intimidation, but to gather evidence for voter fraud claims. Similarly, signs advertising ballot dropbox surveillance are likely to intimidate some voters, especially voters from targeted minority groups, though the intent of those signs is not necessarily to threaten violence (no voter intimidation charges were filed in the 2022 case). However, rumors about armed protestors and potential violence at the polls can also be seeded and/or amplified by opposing political groups (using them to suppress votes of opponents) and foreign disinformation campaigns (seeking to portray democracy as chaotic and untenable). It is therefore extremely important to determine veracity before reporting and/or amplifying this type of rumor. Election officials should work with law enforcement to quickly clarify the on-the-ground situation related to these rumors.

Rumors about the security of ballot dropboxes

Examples:

Rumors around a photo of mail collection boxes at a refurbishing facility, falsely alleging that the boxes had been removed from circulation as part of a voter suppression effort (2020).

A circulating image of ballot drop boxes installed along US border turns out to be satire (2024).

Images spread of a Wisconsin Mayor removing a ballot dropbox from the street, spurred by a political disagreement over who had the authority to install dropboxes (2024).

Explanations: Since 2020, the security of ballots dropboxes have become a significant focus of rumoring during the mail-in voting period. Rumors around “ballot harvesting” (discussed above) often feature ballot dropboxes as an alleged vector for individuals and/or organizations to illegally submit multiple ballots. These rumors often rely upon misinterpretations of legal behavior, e.g. in states where family members are permitted to drop off ballots from other members of their household. In an example from 2023, social media posts misleadingly claimed that a woman was “stuffing” a ballot dropbox in a CNN news clip, because it appeared she had three ballots in hand. Social media users assumed this was suspicious behavior, but in Ohio it is legal for family members to mail ballots for other family members, so the video was not in actuality “proof” of wrongdoing. Dropbox rumors often contain images and video of “suspicious” people using — or just standing near — ballot dropboxes, that are misinterpreted and/or mischaracterized to falsely allege fraud.

Emblematic of the versatility of ballot dropboxes as an object of election rumoring, we have recently seen intentional efforts to connect dropboxes to the larger narrative of “non-citizen voters.” Earlier this year, images circulated social media of what appeared to be ballot dropboxes along the southern U.S. border. Judging by the comments, some users mistook these photos as real images of real dropboxes. This played into larger narratives that non-citizens are illegally voting in large swathes. In truth, the photos were from an article written by the conservative satire website, The Babylon Bee.

Another type of dropbox rumor questions the security of ballots deposited there, alleging that they could be tampered with — e.g. by activists, government officials, and/or the postal service — to remove and delay votes in specific areas. Intentionally or not, these rumors function to sow distrust in the mail-in voting process. In 2020, a prominent rumor spread by left-leaning social media accounts featured an industrial yard full of mail collection boxes and falsely alleged that the USPS had intentionally removed these boxes to suppress votes. The photo was actually taken at a refurbishing facility and the boxes there had nothing to do with the election.

In some cases, actions by activists and/or election officials to either attempt to secure ballot dropboxes or prove that they are insecure are both fueled by rumors of vulnerabilities and produce new “evidence” for rumors that diminish trust in the process. For example, in September 2024, images spread of a Republican mayor carting away a ballot dropbox from outside his office in Wisconsin. This spurred all sorts of rumors about the security of dropboxes and the local district attorney pursued an investigation into the matter. In truth, the mayor had a “philosophical difference of opinion” with the city clerk about who had the authority to install dropboxes. When the mayor removed the dropbox, it had been closed with no ballots inside and was in the process of being installed but had yet to be bolted to the ground. These kinds of actions to “protect” voting infrastructure or highlight its vulnerabilities — in some cases produced to make a point on social media — can breed rumors about election integrity and/or misleadingly act as “evidence” of potential voter fraud.

Machines

For many voters, voting machines are central to the voting process. Yet most people only interact with voting machines a few times a year. Additionally, there are many different kinds of machines and processes. This unfamiliarity and variability can lead to rumors that take a variety of forms, including perceptions that machines are working incorrectly, that they are switching votes, and that they are subject to foreign manipulation or other forms of hacking. Voting machine companies are also active through multiple cycles, meaning that rumors during past elections about particular voting machine and/or voting software companies can be used as evidence to support conspiracy theories about future elections. Below, we outline some subtypes of voting machine-related rumors, and why they can be misleading.

Machines perceived to be switching votes or otherwise malfunctioning

Examples:

Texas voting machines allegedly switching votes for governor from Beto O’Rourke to Greg Abbott in the 2022 midterm elections.

A rumor that voting machines malfunctioned disproportionately where Republicans lived stemming from photographs of heatmaps in an election office, in Arizona in the 2022 U.S. elections.

Rumors that malfunctioning vote tabulators in Maricopa County, Arizona reflected an intentional effort to disenfranchise GOP voters (2022).

Explanation: As early in-person voting begins, we expect to see voters sharing first-hand accounts (and even photos) of perceived issues with voting machines — including claims that machines are switching votes and reports that machines are malfunctioning. Some of the rumors will be false, based upon misinterpreted evidence; in the above Texas case, user error was misinterpreted as intentional software manipulation. But in other cases, these rumors will be at least partially true. Sometimes (as in Maricopa County in 2022) machines malfunction. But the rumors around those issues often mislead by exaggerating the impact of small errors or ignoring remedies such as provisional ballots or alternate locations. We also routinely see conspiracy theorizing about malfunctioning voting machines falsely attribute intent. For example, in the 2022 Maricopa County case, widespread issues with vote tabulators were affecting large numbers of voters, but — despite thousands of social media posts suggesting a conspiracy to suppress election-day voters — there was no evidence of intentionality.

Vulnerability to, allegations of, and/or incidents of hacking voting machines

Examples:

Video allegedly showed a way to hack the federal voting assistance program (FVAP) in 2022, implying ballots from military and overseas voters were vulnerable or suspect.

Evidence that modems used for transmitting results from voting machines could be hacked spread rumors that results could be altered (2024).

A human error that led to initially incorrect election results in a state using Dominion voting machines sparks rumors that the company’s machines were allegedly vulnerable to hacking and manipulated election results in 2020.

Explanations: The probability of a hack disrupting elections is unlikely, but possible, which is a concern for election security professionals not just because of actual security and election integrity issues, but also because it could provide fodder for those who wish to question election results. For example, in 2020 a video featuring an “Iranian whistleblower” circulated, ostensibly revealing a “hack” of a U.S. voting system. The video featured false evidence — it did not contain evidence of an actual software vulnerability — and was part of an information operation attempting to sow distrust in the election. Some election experts note the disruptive potential of “cyber-disinformation” operations that combine a hack, an attempted hack, or false claims of a hack of an election system with a parallel information campaign to mischaracterize the impact of that hack and sow widespread trust in results. But it is important to stress that there is no evidence that foreign hackers have successfully altered vote counts in U.S. elections.

Voting systems that rely upon machines have layers of security to mitigate the threat of hacking (e.g., limiting connections between election infrastructure and the internet) and provide methods for identifying potential issues (e.g., making sure that votes leave a paper trail that can be checked against the machine counts). But well-meaning efforts to identify and address potential vulnerabilities in these systems — vital for ensuring continuous improvement of these systems — often feed rumors that question the integrity of elections that rely upon voting machines.

An interesting case, discussed in news coverage by POLITICO, revealed that unofficial results could, in theory, be vulnerable to tampering when spread over modems. For security reasons, the vast majority of voting and tabulating machines do not connect to the Internet or use other information-communication technology and instead rely upon election officials to physically move data from one machine to another. However, in some states, some machines that are part of voting systems use modems to electronically communicate unofficial results on election night. Though it would not impact the official results, interfering with this communication and tampering with the unofficial results could result in inconsistencies in the public vote counts, which could fuel rumors about untrustworthy election results. Additionally, the fact that some election machines do use remote connections feeds general rumors about insecure elections, and the nuance is often lost that those machines are not involved in the official vote counting.

Some voting machine companies — including Dominion Voting Systems and the Smartmatic company — have become repeated, named targets of election integrity rumors. After the 2020 election, Dominion sued Fox News for defamation (which Fox News settled for $787 million) because of the network’s coverage of rumors alleging the company’s machines were used to commit election fraud. Rumors about Dominion routinely relied upon misinterpreted evidence (where a handful of cases of alleging manipulation of machines were actually human error), and exaggerated impact (claiming issues were far more widespread than they actually were). Given its prominence in 2020 election fraud rumors, we expect Dominion machines to continue to be a major focus of social media rumors in 2024, though perhaps with more careful coverage by media outlets.

Allegations of foreign ownership or manipulation of voting machines

Examples:

Rumors of Chinese interference with voting machines sparked by the October 2022 arrest of Konnech voting machine company CEO Eugene Yu.

Republicans accuse Smartmatic voting machine company of being a project of Venezuela (2020) for the sake of election interference, exacerbated by recent bribery arrest of Smartmatic’s Venezuelan-born co-founder (2024)

Explanation: Another common (and provocative) type of rumoring about voting machines speculates that foreign ownership of election technology constitutes or facilitates foreign interference in U.S. elections. Smartmatic — a company that produces voting systems — was caught up in rumoring about election integrity in 2020, including unsubstantiated claims that the company had “rigged” the election in favor of Joe Biden. These included rumors that their machines were a vector of foreign election interference by Venezuela. (Ironically, in 2017, Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro blamed Smartmatic for bowing to US pressure when it cast doubt on Venezuelan authorities’ election counts.) On September 26, 2024, Newsmax settled with Smartmatic in a defamation case that accused the partisan media outlet of repeatedly publishing false rumors. Smartmatic is also suing Fox News for defamation. That said, the recent arrest of the Venezuelan-born Smartmatic co-founder in an unrelated Philippine bribery case has catalyzed additional rumoring about the company’s election machines, though as of 2020 they were only being used in to support U.S. elections in a single county (Los Angeles, CA).

Another remarkable case involves the October 2022 arrest of Eugene Yu, CEO of the Konnech voting machine company. Yu was arrested for alleged conspiracy and embezzlement by the Los Angeles County DA. The arrest, motivated by false rumors featuring allegations that poll worker (not voter) data was stored on Chinese servers, was seen as “proof” of foreign election interference by QAnon conspiracy theorists on conservative commentators, right before a midterm. These allegations appear to match those made by True the Vote, which claimed to have found — by accessing Konnech’s database without authorization — the company’s data stored on Chinese servers. Yu insisted that no data had been stored in China, and charges against him were soon dismissed. He eventually won a $5 million lawsuit against Los Angeles County in 2024 for damages caused by the arrest, which they claimed was politically motivated. The complexity and intrigue of this case, as well as potential connections between Konnech and other prominent rumors this election cycle, lead us to believe that we will see continued mention of the company this year.

Rumors of foreign election interference via voting technology are likely to persist throughout the 2024 election cycle, often relying upon mischaracterizations of evidence or unsubstantiated, speculative claims.

Voters

Rumors about who is eligible to vote, who is registered to vote (illegally), and who is voting (illegally) constitute a large bulk of narratives during the election cycle. These may include rumors about dead people voting or impersonation. These “ineligible voter” rumors may weaponize other politically charged identity politics because they feature real people and surface discourse about who is and isn’t an American: legally, in perception, and in visibility. This means that latent cultural racism and xenophobia may be weaponized to breed suspicion around the eligibility of certain voters, particularly Black, brown, and Latino ones. At the same time, these rumors connect to other politically charged issues, such as illegal entry of migrants at the southern border. As such, non-citizen voting rumors contribute to a larger story about immigration and who is an American.

Rumors about non-citizen voting and registration

Examples:

Misinterpreted and distorted evidence that migrants entering the country illegally are planning to illegally vote circulates on social media (2024).

Hidden camera videos of Latinos in a Georgia suburb being asked if they were planning to vote are shared by the Heritage Foundation, sparking rumors that non-citizens are voting en masse (2024).

A discredited peer-reviewed paper claimed that non-citizens are voting in large swathes and circulates on social media as evidence of non-citizen voting claims (2016, 2024).

Allegations circulate that Democrats have an explicit strategy to let migrants illegally into the country in order to illegally register them as voters, resulting in the investigation into community voter registration drives in Black and brown communities, as seen in Texas currently (2024).

Explanation: Rumors of non-citizen voting have been a pervasive trope in election rumoring since 2016 and are already playing a significant role in the discourse surrounding the 2024 election. Often, these rumors rely upon manipulations or misinterpretations of so-called “evidence” of non-citizen voting, such as videos of migrants allegedly saying they are planning to vote offered as “proof” of mass non-citizen voting. In some cases, these videos distort what the interviewees are saying, though misleading subtitles. In other cases, the interviews may be recorded under duress, where the subject responds without fully understanding what is being asked, or where the subject says something to get the interviewer to stop asking them questions. A related set of rumors repeatedly resurfaces a discredited academic study to falsely claim non-citizens impact election results. In addition to leveraging manipulated or mischaracterized “evidence”, the false narrative claiming that massive numbers of non-citizens are voting also builds upon smaller rumors that exaggerate the impact of the rare instances in which non-citizens illegally vote, for which penalties include jail or deportation. Similarly, evidence of thousands of non-citizens on the voter rolls being “purged” is often used to support rumors that falsely attribute intent to vote of those non-citizens on the rolls, who may have accidentally registered upon getting a driver's license, when in fact voter roll clean up is a remedy to prevent non-citizen voting.

Rumors about voter impersonation or multiple ballots cast by a single voter

Examples:

A claim by Donald Trump that a single voter may cast a ballot many times, which is illegal, spreads on social media (2018).

Rumors spread that people voting under the names of deceased people, such as Trump surrogates claimed happened in Michigan in 2020, though the allegations were false and/or misleading.

Explanation: Accusations of widespread voter fraud due to impersonation, where a person claims the identity of someone else at the polls, generally turn out to be false. The Brennan Center for Justice has found only 31 instances of impersonation in billions of ballots cast. Rumors about impersonation tend to amplify isolated cases to give a false sense of the issue being widespread. Similarly, claims that dead people have voted are common during elections but are grossly exaggerated, as happened in 2020 in both Pennsylvania and Michigan, and often misinterpret normal events — such as a person dying between the time they cast their mail-in ballot and the time the votes are counted — as signals of fraud. Claims about impersonation and dead voters also fail to note the layers of security and remedies that routinely clean the voter rolls of dead and eligible voters and make it extremely difficult to vote in the name of someone else (and get away with it, especially at scale.

Officials, Workers and Observers

Election and government officials are prime subjects for election related rumors of a variety of configurations. Most rumors surrounding government officials, election officials or administrators imply the administration uses their official position to sway electoral outcomes. These include speculation — without evidence — about election officials leveraging official power to influence election results, taking part in procedural sabotage, and even colluding to aid foreign manipulation. Election observers, including at the polls and the ballot dropboxes, can also become both subjects and vectors of rumors. Poll watchers are people who are not official election workers but are allowed access to election related areas in order to monitor the election process. During the mail-in voting period, self-deployed volunteer observers have in recent cycles been specifically looking after ballot dropboxes. This section explores some of the pre-election rumors related to these figures.

Allegations that election officials are corrupt and/or enable fraud

Example: Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs’s duties include overseeing an election despite running in it, which is seen as evidence of malfeasance in online rumors though it is technically legal and typical.

Explanation: During the 2022 election cycle, the Arizona gubernatorial race between Republican Kari Lake and Democrat Katie Hobbs received a lot of attention from online audiences and media. This is due in part to Lake’s endorsement by Trump and her promotion of claims that U.S. elections are insecure. Hobbs, on the other hand, emphasized the security of Arizona elections — and American elections more generally. Katie Hobbs was also Arizona Secretary of State at the time, a position that contributed to rumoring, because the duties of her role included overseeing the race in which she was running. The AZ Secretary of State supervises the canvassing and certification of election results (after individual counties submit their vote tallies), and this situation of a candidate overseeing one’s own election occurs regularly in Arizona and other states. Nevertheless, claims were spread online that Hobbs’ role as Secretary of State amounted to a conflict of interest that precluded her from conducting her job in an unbiased manner, with calls to recuse herself from her duties to avoid appearances of impropriety — despite everything being legal. In 2018, Democrats similarly asked Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp to recuse himself of this duty, which he declined.

The U.S. Postal Service is manipulating or interfering with the election

Examples:

In 2020, then-President and candidate Trump claimed that the Postal Service could not be trusted to deliver mail-in ballots.

Explanation: Unsubstantiated claims that the USPS purposely slows mail delivery to sabotage the mail-voting process have persisted since the 2020 election cycle. These rumors, which spread in slightly different forms on the political right vs. the left, build upon real concerns — i.e. election officials have warned that postal service delays could negatively impact mail-in voting during the 2024 election, and underscore the challenge of disentangling legitimate criticism from rumor and conspiracy theorizing.

On the political left, these rumors typically focus upon the U.S. Postmaster General, Louis DeJoy, a Trump appointee. In 2020, DeJoy was criticized for his lackluster performance during the election, and many Democrats urged his resignation. In a related court case, U.S. District Judge Emmet Sullivan substantiated some of the critical claims, citing how DeJoy’s policy changes “impede[d]” states efforts to supply alternatives for in-person voting. But there were also unsubstantiated claims that he leveraged his power as postmaster general to intentionally sabotage the U.S. Postal Service and prevent voting by mail. Thus, many of DeJoy’s critics falsely attributed intent to his perceived poor performance as a sign of election tampering, which was not substantiated. DeJoy continues to be criticized by Democratic elected officials for his management of the Postal Service’s handling of mail-in ballots.

On the other side of the political spectrum, there have been — and will likely continue to be during the mail-in voting period — rumors accusing U.S. postal workers of intentionally slowing or discarding ballots. While there have been rare cases of mail carriers discarding mail including ballots, there is no indication that these isolated cases have been politically motivated or that they have impacted the results of an election. When spreading among right-leaning audiences, speculative rumors about corrupt mail carriers are likely to build their case by focusing on locations or vote types (absentee ballots from overseas military personnel) that are perceived to be predominantly Republican and noting that postal unions are historically supportive of Democratic candidates.

Ballot drop box watchers are intimidating voters in their attempts to catch alleged “ballot mules”

Example: People who signed up to monitor ballot drop boxes in Arizona may have intimidated voters after claims that drop boxes are major vectors of fraud (2022).

Explanation: In 2022, Clean Elections USA, an organization dedicated to finding evidence of voter fraud and strongly motivated by the debunked film 2000 Mules, organized grassroots efforts to monitor ballot drop boxes. The primary claim pushed by the movie, 2000 Mules, was that ballot drop boxes are insecure and allow so-called “ballot mules” to drop off large numbers of fraudulent ballots. Along with online rumoring surrounding these issues, members of online audiences were recruited by Clean Elections USA to sign up to watch drop boxes.

Although many of these drop box watchers appeared to be peacefully observing, including having “watch parties,” others were more confrontational or threatening. In particular, photos were taken and spread online of two watchers who brought weapons and wore tactical military gear as they observed drop boxes, as reported by Maricopa County Elections Department. This quickly led to accusations of voter intimidation and were widely spread online. Both the actions of the watchers and the spread of claims of intimidation potentially impacted voters’ decisions on when and where they would vote.

Look out for the next installment of this series, closer to election day!

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Mike Caulfield for his previous work with the CIP, which provided much of the intellectual and archival scaffolding of this work. We would also like to acknowledge the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University for their feedback.

Kate Starbird is a University of Washington Center for an Informed Public co-founder and professor in the UW Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering.

Ashlyn B. Aske is a CIP graduate research assistant and Master of Jurisprudence student at the UW School of Law.

Danielle Lee Tomson is the CIP’s research manager.

Joseph S. Schafer is a CIP graduate research assistant and HCDE doctoral student.

Stephen Prochaska is a CIP graduate research assistant at the UW Information School.

Adiza Awwal is a CIP graduate research assistant and HCDE doctoral student.

Rachel Moran-Prestridge is a CIP senior research scientist and affiliate assistant professor at the UW Information School.

Michael Grass is the CIP’s assistant director for communications.